The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org

October 16, 2024

Aging Immigrants: No Gold in Golden Years

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team

It’s a familiar sight in cities across the US: groups of mostly Mexican men standing in a Home Depot parking lot, hoping that you or I will give them a job for a day. We know they’re undocumented, but we hire them anyway. The meager wages we pay will barely last them a day’s spartan existence — and they still will manage to send money home.

In spite of the demonizing rhetoric, undocumented immigrants play such a commonplace role in our lives that we take them for granted. Remember Zoe Baird, who was nominated for Attorney General by Democratic president Clinton? She broke the law by hiring an undocumented nanny and failing to pay her Social Security taxes. When Republican Mitt Romney ran for president, we learned he had an undocumented gardener. Me? Guilty as charged — I hired a friend to rebuild a porch, and his assistant was undocumented.

There inevitably comes a time when those who work so close to us can no longer perform the job. What happens then? As Nik Theodore learned in hearing the stories of 1500 elders, most have zero income, not a copper penny of their own.

Shouldn’t these workers enjoy some fruits of their decades of labor? Mexico says yes. It has gratefully acknowledged the service of their citizens abroad in sustaining the poorest families and contributing to the national economy. Therefore, it will extend its old age pension benefit to elderly Mexican workers in the US. For those of us who are US citizens, we can demand that the US do the same. Hard-working elders, people we’ve trusted with our homes, gardens and children, deserve some gold for these not-so-golden years.

More Info

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website. And definitely see the new English podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. They entertain, while dismantling the lies and distortions about Mexico fed to us by the mainstream media.

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription.

Running on Empty: Our Undocumented Elders

Nik Theodore is head of the Department of Urban Planning and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He focuses on economic restructuring, labor standards and worker organizing, researching how urbanization is entrenching social inequalities and political-economic exclusion. Among other media, he has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Time and has appeared on CNN, the PBS News Hour, All Things Considered and MarketPlace. He worked with the National Day Laborer Organizing Network (NDLON) on a survey and report about the situation facing older immigrant workers.

What kinds of jobs do immigrants from Mexico do?

Are working conditions different for documented

and undocumented workers?

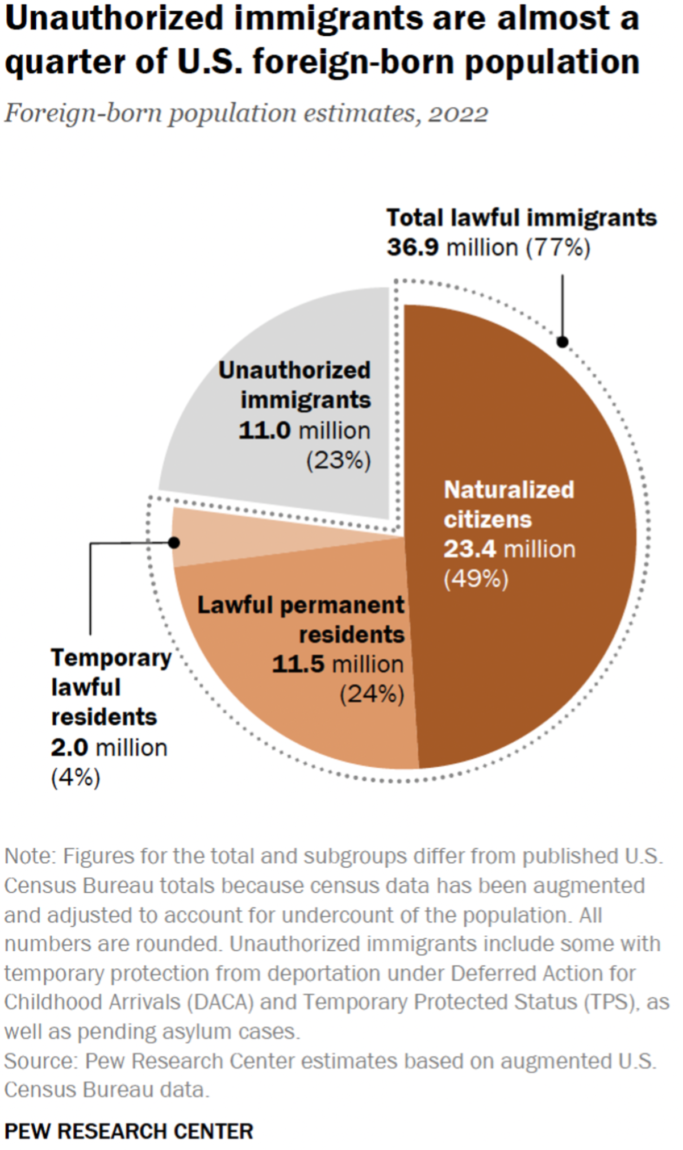

About 10.6 million Mexicans work in the US; we don’t know what percentage of those are undocumented. Besides agriculture, workers are clustered in the growing construction sector — typically, construction jobs are residential and hire non-union workers. Workers are also prominent in domestic work, food service and some manufacturing industries. These sectors are all physically demanding and low-paid; working conditions are substandard and rife with labor abuses. Often employers pay workers under the table. That’s especially true for day laborers, but those with legal papers are only slightly better off. They can at least afford to take more risks, like leaving a terrible job.

In the 1990s, worker centers cropped up to help these non-union, non-citizen workers learn about their employment rights and to organize to improve conditions. While the relationship between unions and worker centers was originally chilly, by the 2000s, in some places, unions and worker centers formed collaborative projects.

For example, LIUNA, the Laborers Union, had an apprenticeship program for immigrant workers. On the East Coast, joint worker centers/union locals were established, but after the recession of 2008, these efforts dried up.

What happens to undocumented workers when they reach retirement age? Is the migrant Mexicano population an aging one?

Even the people at NDLON were surprised at what desperate situations these elders face! On average, our survey’s 1500 people had worked in the US for around 30 years after working about 15 years in Mexico. And after all that time, they had zero — no Social Security, no pensions, no savings, no safety net at all.

Why? Because any money they had over what they required for daily survival, they sent home to Mexico. In just one year, workers sent home to Mexico $66 billion — with a B! — in remittances from abroad. About 97% of these were sent from the US, and they accounted for more than 3% of Mexico’s GDP. Most of the money was remitted to southern Mexico — the Yucatan Peninsula is Mexico’s poorest region, home to one of the highest percentages of people leaving to find work.

In our survey, only 25% of respondents aged 65 and older had stopped working. Of those, the years of backbreaking labor had taken a toll — 72% of “retired” workers have a disability preventing them from working; likely many would have continued if not for the disability.

Most are unable to continue the kind of physical labor they did when younger, so they find marginal jobs like selling from push carts on the street.

Finding an affordable place to rent was tough, and one-third said they couldn’t afford healthy meals. Do they have kids that can support them either in the US or Mexico? Only 10% said their families could care for them; their children have kids of their own and are still working and struggling too.

The hardships we identified are increasing as the migrant population ages. Before, the age demographic of migrant workers was a pyramid — younger workers at the base and relatively few older workers at the top. Today, it’s more like an hourglass. Younger workers keep arriving, and aged workers are stuck in place.

Your report makes the case for extending Pensión Bienestar (Pension for the Welfare of Older Adults) to older Mexicans living in the US. Why do you focus on a Mexican pension for your recommendations?

People heard president Lopez Obrador say at a press conference that the “country owes a debt to migrants.” He often thanked migrants for their contributions to the Mexican people and to its economy. So, migrants thought, yes, we agree — perhaps Mexico can repay that debt by extending pension benefits to us!

A few weeks ago, NDLON brought a group of elderly immigrant workers to meet with Mexican legislators and request that pensions be expanded to include them. They found that most Mexicans they talked to have a rosy vision of life in the US and were surprised to hear of the hard reality of their lives. AMLO did announce that the PensiónBienestar program would be expanded to include retired Mexicans in the US, but the government hadn’t yet implemented the expansion.

However, NDLON and other immigrant rights organizations aren’t ignoring the US’s responsibility. We’re asking for Social Security reform. Since undocumented immigrants can’t collect Social Security, billions of dollars have accumulated in the Social Security trust fund that these workers cannot claim. It’s unbelievable that this old age benefit can’t be assigned to those who earned it. NDLON also called on the US president, through executive action, to allow workers to qualify for deferred action (deferring deportation) if they’ve worked in the US for decades. As a start, NDLON recommends that the Government Accountability Office review the social security system to make it fairer.

A positive development is the Delayed Action for Labor Enforcement law, which became effective in January 2023. If a person suffered from a labor violation in the past — for example, wage theft — they can file a complaint. Resolution can include deferred action and regularizing the worker’s immigration status.

Life for elder undocumented immigrants is full of hardships and insecurity. Given the negative climate in the US, they and their supporters are preparing for a self-help infrastructure.

However, the ray of light is Mexico, with the promise of Pensión Bienestar payments. We can hope for speedy implementation under Mexico’s new president, Claudia Sheinbaum. Mexicans are looking homeward for a helping hand.

Claudia Sheinbaum, Presidenta

Writer, playwright, and journalist Kurt Hackbarth is a naturalized Mexican citizen living in Oaxaca. He writes for Sentido Común, Jacobin, and co-hosts the Mexico Solidarity Project’s Soberaníapodcast. Excerpted from Jacobin, Oct. 2, 2024